Managing your professional decline

Professional athletes are setup for failure when it comes to their professional identity.

Think about it.

Most athletes hit their athletic prime when they're relatively young, qualifying for the olympics and making the podium when they're in their teens or twenties, and then what?

After they hit the peak of their success and gain accolades, most "retire" and move on from the grind of rigorous training and competing schedules.

Then what?

Who do they become next? (Think Lance Armstrong or Tanya Harding...)

This is one reason the hashtag #morethananathlete has gone viral and started an entire movement.

Professional athletes go through deep identity despair and flounder before finding a path forward. They must invent a new professional identity and brand for themselves. Not an easy task.

The higher you climb and the more your identity is tied to your career achievements, the harder the fall hurts when you inevitably lose that identity.

Arthur Brooks says it best in his article. He calls it "The Principle of Psychoprofessional Gravitation" which means:

"The idea that the agony of professional oblivion is directly related to the height of professional prestige previously achieved, and to one's emotional attachment to that prestige. The Principle of Psychoprofessional Gravitation can help explain the many cases of people who have done work of world-historical significance yet wind up feeling like failures."

Athletes aren't the only ones who go through this, they're just an easy group to point to.

Arthur Brooks starts his article by describing a conversation he overheard on an airplane in the row behind him. He heard an older man who was obviously sullen and down on himself. When it was time to deplane, Brooks was able to see who the man was. Surprisingly, he recognized him as being world famous and accomplished.

Brooks thought to himself, "How could this person feel so self-defeated when the rest of us admire who he is?"

This is the predicament of identity.

Feelings of relevance and irrelevance.

Being in touch with our self-worth and then losing it.

Yes, it's hard to live up to our expectations of ourselves, especially if we hold ourselves to high standards.

Researchers conjecture that some of the [extreme] loss we feel is due in part to our memory of our remarkableness when we're at our height.

HOW TO HANDLE DECLINE

Accept the inevitably of professional decline.

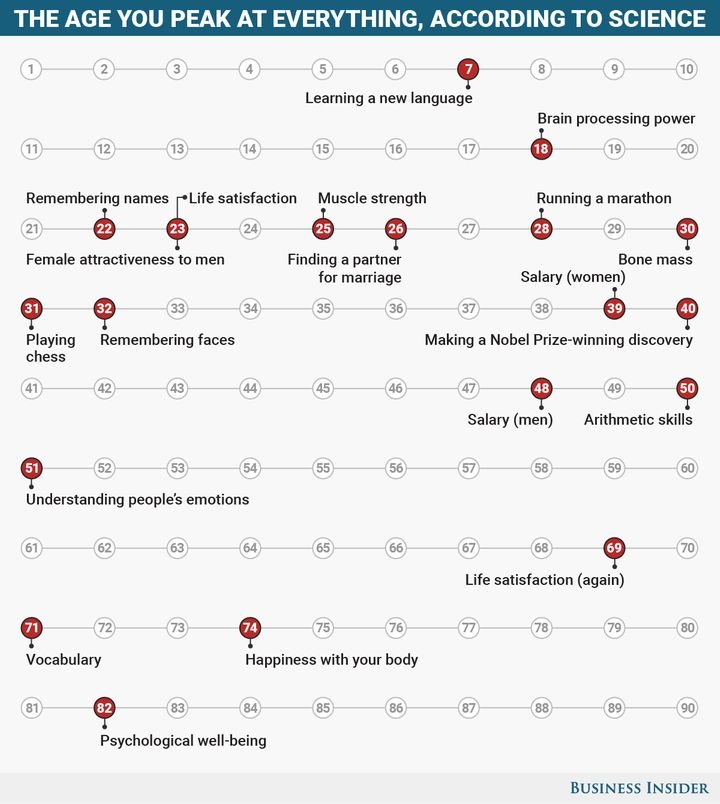

There are peak ages for everything (give or take a few years and the kind of field you've chosen). Here's a chart that captures a few.

Peak ages aren't a hard and fast rule, it's a rough guide of averages.

Knowing you'll inevitably reach a peak in your career isn't meant to cause gloom, it's a reminder that you'll inevitably need to reinvent yourself. It's part of the process of growing and aging.

That's why I believe so deeply in giving people tools to know how to reevaluate their professional identity whenever that time arrives. For many of us, it will happen multiple times in life.

Brooks writes,

"I am lucky to have accepted my decline at a young enough age that I could redirect my life into a new line of work. Still, to this day, the sting of that early decline makes these words difficult to write. I vowed to myself that it wouldn’t ever happen again."

Brooks also points out a huge takeaway,

"When Darwin fell behind as an innovator, he became despondent and depressed; his life ended in sad inactivity. When Bach fell behind, he reinvented himself as a master instructor. He died beloved, fulfilled, and—though less famous than he once had been—respected."

Who do you want to be? Darwin or Bach?

Lastly, one of my favorite quotes from Brooks is this (it's pure gold!):